Earlier this year, I read Gionathan Lo Mascolo’s edited collection The Christain Right in Europe: Movements, Networks, and Denominations. I’d initially intended on skimming a couple of chapters but ended up reading it cover-to-cover. The book is an essential resource for anyone trying to understand the global reach of Christian nationalism and connections between the United States and Europe.* Gionathan was kind enough to give an interview in which he discusses several of the essays and issues discussed in the volume.

Wondering how the Nashville Statement influenced Dutch churches? Trying to understand what’s going on in Hungary, or with Putin, the Russian Orthodox Church, and Russian Christian nationalism? Want to learn about a new organization, Faith in Democracy, which Gionathan has helped found to address this global challenge?

Read on…

(Read to the end for a few extra tidbits.)

Having observed various expressions of the Christian Right in Europe over the past several years, I found this volume enormously helpful. The 21 case-study chapters on different countries were highly informative and accessible even to the lay reader. Can you describe the origins of this book, and who your intended audience is?

The motivation for this book arises from two phenomena I observed in Europe over the past decade. First, secular far-right parties have significantly influenced political institutions and mainstreamed their ideology by strategically adopting Christianity's symbols and language to mainstream their ideology. They portray a Christian Europe under threat from moral liberalization and Islam. Second, while working as a researcher and campaign organizer, I observed a process of politicization and radicalization within many Christian communities across Europe. Regardless of national context, history, or denomination, I encountered remarkably similar narratives shared by preachers, pastors, and activists both in churches and online. These narratives include warnings about the dangers of Islamism and refugees, perceived threats to Christians and the West from the LGBTQIA* community, and a growing rejection of democracy and the freedoms it guarantees.

European observers struggle to recognize the Christian right's rise in their own countries because they are accustomed to more clear connections and influence of the Christian Right in the USA. These networks have also been difficult to spot because they adapted to European norms and taboos concerning the relationship between religion and politics, as well as the nuanced dynamics between parties and churches. They often shy away from public visibility to secure continued political success and influence in an increasingly secular society.

Therefore I decided to compile an edited volume that would analyze this new dynamic across as many countries as possible. Each chapter meticulously deciphers the networks among parties, movements, and churches, offering a transnational perspective that unveils the true extent of this movement. This wealth of information, encompassing names, networks, and quotes, is accessible to academics, policymakers and church activists, enabling them to recognize this shift in their environments and identify the people responsible for this dangerous development. Additionally, it should be approachable for readers without an in-depth knowledge of European politics and religion, and also offered as a free ebook for those at the grassroots level and researchers who might not be able to afford a copy but still rely on the research of the outstanding authors who made this book possible.

In your introductory chapters, you counter the suggestion that there is nothing new about the Christian Right in Europe and argue that this is not merely the case of traditional Christianity persevering in the midst of an increasingly secular society. Instead, you point to three factors that distinguish the Christian Right from mainstream Christianity. Can you briefly describe those for us?

The novelty of the Christian Right in Europe manifests in three factors: ideology, institution, and strategy.

Ideologically, the Christian Right in Europe has undergone a thematic concentration. Notably, it has embraced the culture wars, vehemently opposing reproductive and gender identity rights and advocating for a return to 'patriarchal, traditional family structures.' This turn has proven effective for transnational collaboration and finding a strategic place within the far-right galaxy. Christian supremacy, nationalism, and anti-Muslim racism are central narratives. Theologically, the embrace of religious nationalism and the ferocity, hate, and disenfranchisement directed toward the LGBTQIA+ community represent a departure from Christian values. It is an idolatry that elevates the nation-state above Jesus' teachings and outright rejects human dignity and the commandment to love your neighbour as yourself.

Institutionally, the Christian Right exhibits two remarkable features previously unseen in the European landscape. Firstly, the intensity of transnational networking is historically unusual, especially within the far-right context, where traditional national chauvinism normally prevails. Secondly, there is a surprising interdenominational collaboration between Christian Right actors, marking a significant departure from the past when conflicts between denominations profoundly shaped European history. This collaboration between ultraconservative Catholics, Orthodox Christians, and Protestants—former adversaries in churches and on battlefields for centuries—forms what has been described as an "Ecumenism of Hate."

Strategically, the Christian Right has renewed its tactics. This includes the establishment and professionalization of Christian Right NGOs, the adoption of lawfare tactics to use legal contestations for political and social change, the use of secular language to disguise their religious agenda, and the utilization of astroturf for strategic advantage—a deceptive practice aimed at obscuring the movement's true origins and funding, often provided by US and Russian oligarchs, to mislead the public. These strategies bear the unmistakable influence of the US Christian Right, reflecting its impact on the European Christian Right and the globalization of the American culture wars.

The book contains numerous examples of the influence of the American Christian Right on European movements. Journalists like Katherine Stewart have been tracking the influence of the World Council on Families, and the WCF makes frequent appearances in this volume. What is this organization, and where do we see its influence in the European context?

World Congress of Families is a central player in the global Christian Right and exemplifies the globalization of the American Culture wars. Established in 1997 by US and Russian civil society actors, it operates from the US under the International Organization for the Family. In Europe, it plays three significant roles: Firstly, through its well-known annual summits, which were mainly held in Europe during the last decade, it has normalized fringe Christian Right and anti-gender activists by bringing them together with emerging conservative and far-right politicians. These events have been hosted by government representatives in Italy and Hungary, among others.

Secondly, the WCF leads in crafting successful strategies that originate from the US Christian Right, including the aforementioned transdenominationalism, the use of a religious moral language that is devoid of theology, and close ties with business and billionaires, such as the Russian oligarchs Vladimir Yakunin and Konstantin Malofeev. These Russian oligarchs with close ties to the Kremlin and the Russian Orthodox Church use the WCF and other organizations to covertly finance anti-democratic, anti-gender organizations, which present themselves publicly as grassroots movements and ideologically support far-right parties. Leveraging such financial and political connections, the World Congress of Families has additionally significantly influenced anti-LGBTQIA* legislation in Russia, Nigeria, and Uganda over the past decades and made civil society activism more difficult.

In connection to the WCF (and as someone who has been accused of being a “cultural marxist” more than once), I found the story of Alexey Komov pretty wild. Can you tell us who Komov is and how we end up with Komov claiming to be anti-communist and pro-Stalin?

Alexey Komov's interpretation of history is indeed quite unconventional, and I appreciate Kristina Stoeckl's inclusion of her research on him in her chapter about the Christian Right in Russia. Komov, originally a business consultant, joined the WCF in 2008 as part of a generational renewal, which saw a strengthening of the relationship between the WCF and the Russian Orthodox Church, as well as with oligarchs like Konstantin Malofeev, whose right-hand man Komov has become. Since then, the US-educated Komov has risen to lead the Russian section of the WCF, and he and his wife are the founders of the Russian homeschooling movement.

As documented by Stoeckl, Komov frequently repeats a story at various events, portraying Russia, despite its low church attendance numbers, as a global bastion of Christian values. According to him, Bolshevism was a Western imposition aimed at destroying Russia's families and national unity through the introduction of abortion and feminism. Komov further claims that Stalin intervened to suppress the progressive Trotskyists and reinstate the patriarchal model and patriotism, thus saving the Russian people. Furthermore, Komov claims that in the West, Trotskyists later embraced the strategies of Antonio Gramsci and the Frankfurt School, paving the way for the sexual revolution of the 1960s, now perpetuated by entities such as the United Nations, Bill Gates, and the European Union.

This revisionist view of ideological history is not only highly problematic and anti-intellectual but also serves the agendas of these movements, offering a historical revisionism that sustains Russian Christian Nationalism. It presents Russia as a defender of Christian values against the morally corrupt West, a narrative repeatedly used by Putin and the Russian Orthodox Church to justify the invasion of Ukraine. By doing so, Stoeckl concludes that this narrative reshapes Russia's image, portraying it as the true victor of the Cold War.

As a Dutch Reformed Christian myself, the chapter on the Netherlands hit home for me in a number of ways. Jesus and John Wayne has been covered by several Dutch outlets, and now I have a better understanding why. Can you talk about the influence of American evangelicalism on Dutch Christianity, and particularly the impact of the Nashville Statement?

Globalization, particularly within Protestant contexts, has led to the hegemonic dominance of English-speaking churches and religious leaders, exerting increasing influence on theology, liturgy, culture, and consequently politics. Dutch churches are no exception to this trend; on the contrary, they foster historically deep-rooted and traditionally close relationships with reformed and conservative partner churches in the US.

Within the fragmented Dutch religious landscape, the Nashville Statement that was issued in 2018 found considerable attention within various conservative reformed churches. The translated version of this statement, condemning homosexuality and "non-traditional" gender roles and identities, was signed by a wide array of conservative church leaders and university professors.

In her chapter on the Christian Right in the Netherlands, Marietta van der Tol illustrates how Dutch supporters were particularly struck by the stronger stance against homosexuality in the US, in contrast to the growing acceptance of these issues within Dutch conservative churches. The statement reinforced more conservative voices in the Netherlands.

The publication of the statement and its signatories sparked significant outcry and discussions among conservative circles, as the website of the Nashville Statement referenced ultraconservative US groups such as the Southern Baptist Convention, as well as other actors of the European Christian Right, highlighting overlaps with Dutch religious figures who continue to share conspiracy theories on social media.

I was fascinated with the story of Hungary’s Faith Church. Can you give us a very brief history, and do you think this might be a harbinger of future church growth in other European countries?

Faith Church is a Pentecostal community in Hungary and is believed to be the largest megachurch in Europe, with Sunday services broadcast to tens of thousands of households on television and online through its family-run media empire. It was established in 1979 by Pastor Sándor Németh, who received training at Good News Church in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. The church experienced rapid growth after the fall of the communist system, when Hungary entered the liberal market economy and Faith Church adapted by preaching the prosperity gospel. After Viktor Orbán’s landslide victory in 2010, Faith Church shifted its focus again, this time strongly supporting Orbán’s illiberal policies, providing religious legitimacy as he eroded democracy and the rule of law. In their chapter on Hungary, Armin Langer, Zoltán Ádám, and András Bozóki detail how Sándor Németh has openly endorsed Orbán in subsequent elections and advanced Christian Nationalism, anti-immigration rhetoric and Christian Zionism.

Today, Hungary has become a kleptocratic, authoritarian “Frankenstate”, a success that is deeply tied to the employment of Christian Right strategies, narratives, and tactics. While Orbán is praised by the Christian Right in the US as a savior of Christianity, he has dismantled democracy, financially blackmailed religious organizations, and oppressed and even incarcerated church officials and clergy who don’t bow to his demands.

Are there additional ways the American Christian Right has influenced the European Christian Right that we should be aware of?

While many evangelical churches in Europe may not reach the scale of English-speaking megachurches, they are still significantly influenced by them, particularly in language, style, theology, and eventually politics, as they attempt to replicate this success. This influence extends from traditional evangelical and Pentecostal congregations to charismatic church plants inspired or led by global megachurches, as well as Protestant and even Catholic churches trying to counter secularization by adopting new liturgical styles and actively courting young people.

The widespread popularity and impact of English-language worship music and Christian influencers online within church circles often serve as an accessible and sometimes unconscious entry point that strengthens patriarchal and reactionary societal norms, fundamentalist theology, culture wars, purity culture, Christian Zionism, and anti-liberal tendencies within their own church traditions. As they wrestle with these narratives and try to emulate the success of American evangelicalism, they incorporate criticism of religious and democratic pluralism, the guaranteed human rights of LGBTQIA* individuals and people of different faiths and origins, and the collaborative model between state and church. This process can lead to radicalization and make them receptive to far-right parties in their own countries, that strategically reproduce Christian narratives for political gain.

Given the effect of transnational networks on the global Christian Right, do we see any sort of organized, transnational opposition coalescing on the Left, or the center? If not, what might that look like? What strategies could effectively counter the growing power of the global Christian Right?

Currently, movements that counter the Christian Right around the world are inadequately equipped to counter the massive global networks and political connections as well as seemingly bottomless funding that the Religious Right commands globally. This makes it difficult for activists and people of faith in places like Brazil, Poland and India to stand against this overwhelming force.

To bridge this gap, the Rev. Jennifer Butler and I have established Faith in Democracy, an organization currently in its pre-launch phase, committed to empowering and equipping religious groups worldwide in their fight against religious nationalism, and to sharing and implementing transnational best practices, strategies, tactics, resources and digital tools as quickly and effectively as possible. Faith in Democracy will address the greatest unutilized potential to counter religious nationalism: transnational collaboration. Too often, the word "nationalism" leads to the mistaken belief that it is a national problem—a massive misconception that hinders effective engagement with these transnational networks.

One narrative that needs to be interrupted, as it hinders the effectiveness of counter-movements, is also one of the most successful narratives of the Right, which has been to convince the public that religious faith and progressive politics are incompatible and fundamentally opposed. A brief look at history reveals why this lie has been so prominently pushed: many crucial political movements resisting or abolishing tyrannical regimes were driven by people motivated by their religious beliefs in social justice and liberation for the oppressed. These movements often involved coalitions between progressives and moderates who adopted an issue-driven “broad church” collaboration to fight together against imminent threats. These individuals frequently criticized religious institutions and their oppressive hierarchies, which often sided with the powerful.

Today, religious nationalism is central in aggravating three of humanity's greatest challenges: the climate crisis and the resulting poverty and conflicts, rising social inequality, and the decline of democracy, with severe consequences for refugees, religious freedom, and human rights.

As someone who has spent over a decade in campaigning, it is clear that these problems, perpetuated under the banner of religious nationalism, cannot be combated without the participation of people of faith and churches. Faith in Democracy will work towards establishing alliances between secular and religious forces dedicated to democracy. These alliances must be resilient enough to endure significant differences and tensions, such as being appealing both to moderate forces as well as address the responsibility of capitalism. They must counter the threat from the far-right to democracy without defending a status quo that is failing the majority of humankind.

Yet, especially in Europe, there is a lack of understanding between secular and religious groups. Many people on the Left have been overly attached to secularization theories and are blinded by their own secularized, Euro-centric views. As a result, they have underestimated the danger of religious nationalism and the potential of people of faith as political allies. They have overlooked the increasing religious pluralization in Europe and the fact that an increasing number of people, currently more than 80% of the global population, identify with a religious group. It is critical that all entities seeking to combat democratic backsliding partner with pro-democracy religious leaders and work transnationally to overcome the narratives and collaboration happening among religious nationalists and autocrats.

There is such a wealth of information in this volume. In your assessment, what are the key lessons scholars of the American Christian Right can learn from this research?

The Christian Right and Christian Nationalism is not a national challenge but has global ramifications that operate across religious and cultural boundaries. Narratives, talking points, trends, strategies, and tactics are translated, adapted, and implemented at breathtaking speed. This has important implications for the analysis of networks and ideologies: looking exclusively on the U.S. will provide increasingly less insight into how the US Christian Right is evolving.

While the rise of Christian NGOs and faith-based culture wars in Europe reflect significant US influence, they also demonstrate a reciprocal exchange where European right-wing populism has shaped American political strategies. Anti-immigration and anti-elite populism, which gained traction with Trump in America, has been heavily influenced by European right-wing populist ideas. Similarly, global trends from other religions will increasingly behave in the same way. Analyzing and implementing countermeasures will become more challenging without a greater focus on international perspectives. This global spread of the Religious Right requires a reevaluation of traditional strategies used to understand and counter these movements. Scholars must integrate more international perspectives into their research to fully grasp the scope and influence of these ideologies.

To foster transnational solidarity, it is critical to build networks that can share resources, strategies, and support, particularly in regions hardest hit by faith-based culture wars and rising authoritarianism.

The Christian Right in the U.S. has understood the role of transnational exchange for a while and is ahead of scholars and human rights advocates. Their interest and courtship of power holders in Hungary or Russia show their eagerness to learn how it was possible, even in increasingly secularized societies and without popular support, to replace democracy and the rule of law with an autocratic system.

*Note: An earlier version of this post misstated that the book was originally published in German; it was originally published by a German publisher, but in English.

***

Thanks to many who have signed up for our new collaboration, The Convocation, and who tuned into our first podcast episode! And welcome to new readers who have found me through The Convocation—good to have you here!

Please consider joining Gionathan and Jennifer Butler in their Faith in Democracy effort. I know many readers are looking not just for things to read, but also for things to do to help foster better conversations, to counter the creep of Christian nationalism, and to protect our democracy. I’ll be sharing a number of efforts here in the coming months.

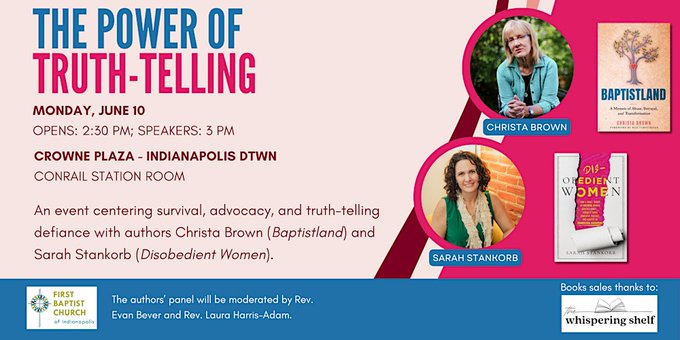

For those in the Indianapolis area, I wanted to invite you to a wonderful event next week. Christa and Sarah are powerful voices combatting abuse in Christian churches, and they’ve paid a heavy cost for doing so. Showing up to support them does more than you know to replenish their strength and strengthen their resolve. Register here.

This makes SO MUCH SENSE! It is not just the united States and it never has been. We are just the last to understand it.

You are one of a handful of people who, if you recommend a book, especially on your topic of expertise, I read it without question.