A few weeks ago, I was sitting in an archive reading the correspondence between Elisabeth Elliot and Letha Dawson Scanzoni, wondering what might have been. There was a time when both women found themselves on the same page with respect to the question of women’s roles in the church. In time, however, their paths diverged. Elliot became one of the leading anti-feminist voices, helping spawn both complementarianism and “purity culture.” Scanzoni became the leading evangelical feminist of the modern era, even if evangelicals might claim she was no longer one of them.

I had the opportunity to meet Letha several years back. In 2016, I attended a Christian Feminism Today conference, the organization (formerly Evangelical Women’s Caucus) Scanzoni helped build. I was presenting on my first book, A New Gospel for Women, and as a historian of Christian feminism, it was wonderful to meet Letha in person. She was warm, engaging, full of energy, and looking for ways to support other women in any way that she could.

As I was reading her words in the archive, I thought back to our time together. “I should get back in touch with Letha,” I said to myself, thinking it would be fun just to compare notes on things. Only a few weeks later, I was saddened to hear of her passing. I wanted to write something a couple weeks back, but didn’t have quite the right words. I looked in my files for the selfie I took with Letha, but couldn’t seem to find it. One of her friends reached out to me to be sure I’d heard of her passing, and sent me a picture she had taken of the two of us in 2016. I would have loved to have carried on this conversation.

Last week, while still thinking over what to say, I got a call from Penelope Green of the New York Times, who was writing Scanzoni’s obituary. We had a long conversation where I was able to explain to her the ins and outs of evangelical theology, the concept of inerrancy, what Scanzoni had meant to Christian women, and how we might understand her legacy. At one point in our conversation, she asked if I might be considered Scanzoni’s heir. I said I was just a historian, and that Rachel Held Evans should more properly be considered the one who carried forward her legacy, but in some ways, I think I could also place myself in her tradition.

To learn more about Letha and her impact, visit Christian Feminism Today to read the many tributes.

And here’s an excerpt from the New York Times obituary, which appears on today’s front page:

Letha Dawson Scanzoni, an evangelical author who argued, gently but persuasively, that the Bible considered women equal to men, inspiring a wave of Christian feminism and, perhaps inevitably, a backlash against it, died on Jan. 9 in Charlotte, N.C. She was 88.

Her death, at a skilled nursing facility, was from congestive heart failure, her son David Scanzoni said.

Betty Friedan’s “The Feminine Mystique” was already a best seller in the mid-1960s when Ms. Scanzoni began writing for Eternity, an evangelical Christian magazine that often challenged conservative attitudes on social issues. She had the same questions as her secular sisters: Should women be submissive to their husbands and stay out of leadership roles in the church, as many fundamentalist Christians believed?

Ms. Scanzoni did not think the Bible supported these views — and quoted scripture to prove her points in articles published in Eternity, like one titled “Women’s Place: Silence or Service?” and another on egalitarian marriage.

The articles didn’t accrue too much opprobrium at the time, though the editors did ask for a photo of Ms. Scanzoni and her husband to accompany the egalitarian marriage piece to show that he approved of her position. And there were a few outraged letters to the editor. One reader wrote that “Mrs. Scanzoni’s article is a prime reason the Apostle Paul told women to be silent.”

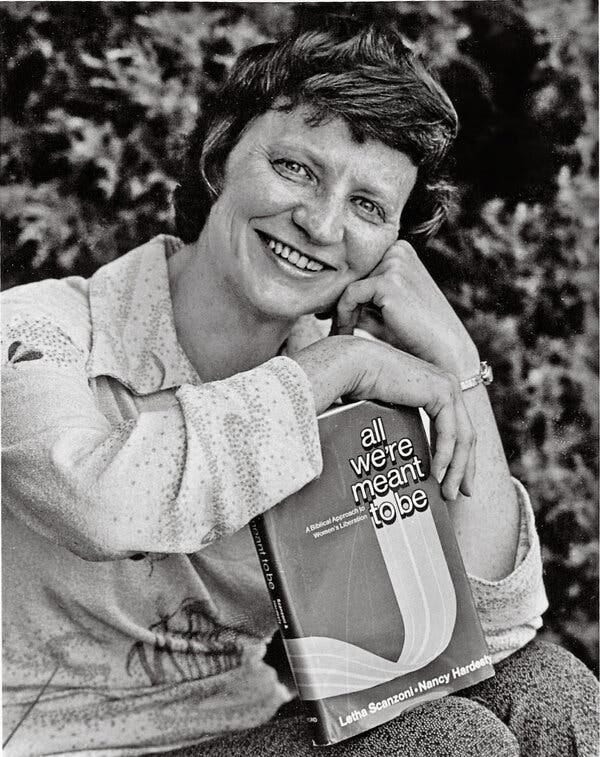

But as the women’s liberation movement gained momentum outside the church, Ms. Scanzoni felt that Christians were sitting on the sidelines, save for some mild carping about the decline of society, and decided to tackle the subject in a book. What resulted was “All We’re Meant to Be: A Biblical Approach to Women’s Liberation” (1974), which she wrote with Nancy Hardesty, who had been an editor at Eternity.

The book became a manifesto for evangelical feminism, using a hermeneutic analysis of the Bible, interpreting the text by noting the context in which it was written and extrapolating its tenets to modern life.

The authors’ opening salvo was to point out that Jesus had had a lot to say about liberation and that his essential mission — and here they quoted from the New Testament — was “to set at liberty those who are oppressed.”

Eternity magazine declared it “the book of the year” in 1975, and Ms. Scanzoni became a sought-after speaker at Christian organizations and a founding member of the Evangelical and Ecumenical Women’s Caucus (now called Christian Feminism Today), a networking and social justice group for the movement that she had helped fire up.

The backlash was immediate, said Kristin Kobes Du Mez, a Christian historian and author of “Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation” (2020).

“Conservatives doubled down in their opposition to women’s rights,” Ms. Du Mez said by phone, “making male headship and female submission defining features of modern evangelicalism. Letha was such a threat because she presented her case for feminism in evangelical terms, making it hard for critics to depict feminism as a wholly secular movement intent on undermining traditional Christianity.”

It was an honor to pay tribute to Letha Scanzoni in this way. May her memory be a blessing.

"At one point in our conversation, she (Penelope Green of the New York Times) asked if I might be considered Scanzoni’s heir. I said I was just a historian, and that Rachel Held Evans should more properly be considered the one who carried forward her legacy, but in some ways, I think I could also place myself in her tradition."

My late wife of 42 years, Jeannette Brownson, never called herself, but always carried herself, as a Evangelical Christian Feminist.

Could I be considered, after her death from pancreatic cancer in 2022, as one who carries forward her legacy? I am a University of Michigan trained historian and a lifelong Reformed Church in America pastor. Other women in business, like her daughter, represent her better. Still, I hope as I continue without her, our daily practice of reading through the Bible and writing about it, that I could at least "place myself in her tradition".

https://substack.com/@bbcandme?utm_source=profile-page

Went to Fuller in 1983. Ms scanzoni and Ms. Hardesty were anchors for our fledglings Feminist Christian pursuits. Admin and faculty were not exactly thrilled with our Women’s Concerns Committee. May her life be a blessing. Thanks be to God for such strong women who paved the way a little farther.