Exit polls reveal a familiar story: around 8 in 10 white evangelicals voted for Trump (as did around 6 in 10 white Catholics and mainliners).

In Time magazine this week, Robert Jones sums up the results:

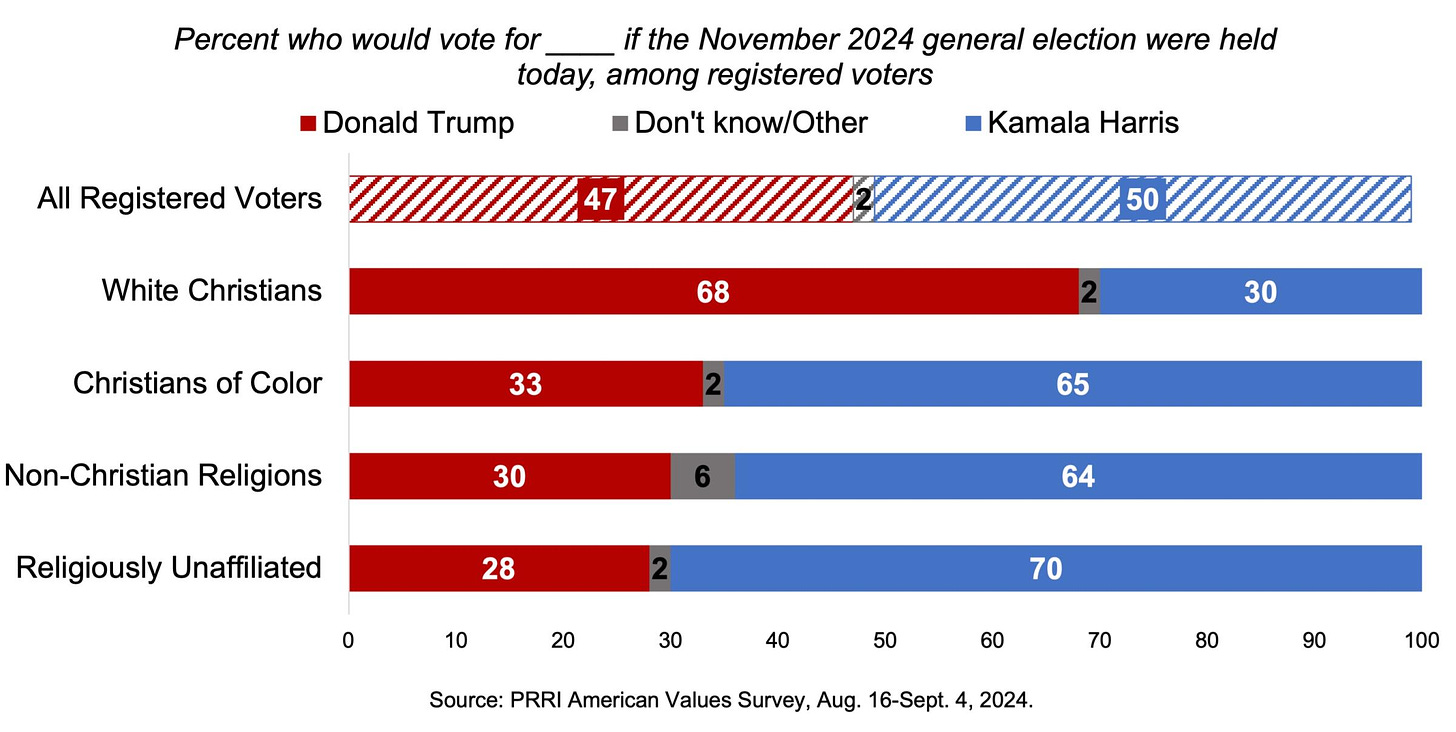

If we put white Christians’ strong support for Trump into context, we can clearly see their singular contribution to his power. Overall, more than two thirds (68%) of white Christians favored Trump over Harris—a mirror image of the rest of the country, including Christians of color (33%), followers of non-Christian religions (30%), and the religiously unaffiliated (28%). While the proportion of white Christians in the country has been declining over the last three decades, they remain 41% of the population and an even higher percentage of voters. Even a modest decline in the overwhelming level of support for Trump among white Christians would have denied him the Republican nomination or the presidency.

For Christians who are deeply troubled by this strong show of support for a candidate and platform that seem to undermine core Christian teachings, the decision to attend church the Sunday after the election was a fraught one. Some pastors, too, wrestled with whether or how to address our political reality from the pulpit.

I went to church on Sunday without giving much thought to what to expect. I may be in the minority on this, but I’d rather hear a sermon that opens my own eyes to biblical teaching than one that confirms my priors, and, all things being equal, I tend to prefer the practice of unflinchingly preaching gospel truth day to day over tailoring messages to the political or cultural moment. Which is to say, because of my church’s consistent witness through word and deed, I didn’t need to hear a sermon hitting the election results head-on. I just needed to be reminded of timeless truths.

It turns out, this sermon did both.

You may recognize my pastor, Len VanderZee, from my recent film For Our Daughters. He was generous enough to agree to appear in the film even though I warned him there could be some blowback. Truth be told, after the film released, he admitted to being a little befuddled by all the positive attention that came his way from survivors—including those who’d left the church behind because they’d never heard words like his from their own pastors. To him, there was nothing magical about his words. “I’m just preaching the gospel,” he said.

On Sunday, he did the same. I’ve excerpted some sections below, but it’s best watched in its entirety at the link above.

The day’s text was from Acts 17: 16-34, the story of Paul standing before the Areopagus in Athens.

Here’s Len, bringing us into the story:

It’s the place where Socrates once stood,

So here, the best, most supple mind in the early church faces the best minds of Greco Roman culture and philosophy.

Paul just happens to be in Athens. He's waiting for some companions to go on to Corinth. Most people would take this an opportunity to just be a tourist. Wandering around the Parthenon and gawking at all those the stunning marble statues of the gods and goddesses. They probably still had all their arms and heads.

Paul is no tourist. Behind the beautiful, artistic facade Paul saw idolatry. He believed to the soles of his Jewish feet that we were created to glorify the one and only true God, creator of heaven and earth.

To Paul, all this Athenian idolatry wasn't beautiful, it saw ugly. It detracted from the glory of the one true God and degraded the men and women who worshipped them. Luke tells us Paul was deeply distressed.

So, Paul was did what he always did. Starting with the Jewish synagogue, but soon spreading out into the agora, the public square, he debated them about what was wrong with all this idolatry.

…Paul’s speech is an amazing piece of classical rhetoric. What Luke gives us here is undoubtedly a summary of a larger address. (What’s written here only takes a minute or two.) It’s an example of Paul’s preaching to cultured pagans. And it still serves as a model for us.

And this Jew, aghast at idols, starts out by patting them on the back. “I see that you are very religious.” Paul doesn’t launch into a harangue against idol worship. He starts with a strange example.

“I happened to see this altar inscribed, 'to the unknown God'" And the grey heads of the Areopagites begin to nod in recognition.

That altar to an unknown God rested on an event, probably half legend, half-truth, that had happened six centuries earlier in Athens. Epimenides, the great Philosopher, was consulted during an Athenian plague. How could they get rid of it? They had sacrificed to all the gods in their pantheon.

Epimenides, in his great wisdom, suggested there might be some “unknown god” who was bringing this judgment on them. So they immediately erected altars to this unknown god, and the plague came to an end. It was a sort of religious CYA.

So here was Paul’s starting point, the connection that he needed for some communication to take place. It's about a God we all know in one way or another, even if we only know him as the unknown god.

…And Paul wasn’t just reading the Bible, he was reading the great poets and philosophers of the culture. He was. reading the newspapers and observing the billboards of his day. He knew that that’s where we find the soulful longings of a people, the glimmerings of truth they have in their hearts.

This is what good missionaries do. They immerse themselves in a culture so they can speak the same language as those we are trying to reach. Effective Christian witness doesn’t just thump the Bible, it must also exegete the culture in order to address its longings.

Paul begins by pointing to God’s greatness as the source and goal of all things. He tells them of the God who does not live in temples made by human hands.

And then he deftly quotes one of their great poets, God not far from us. is the one “in whom we live and move and have our being.”

I love that phrase. God is not a being alongside others. God is being itself. All that exists does so within the being and life that God gives.

I think that many people reject the gospel today not because they see it as false, but because they see it as trivial. Many Christians tend to talk of a personal Savior, and offer a way out of this world to heaven.

For Paul, the gospel isn’t just some religious comfort, it’s the story of history; it’s the drama of God’s great cosmic purposes.

The gospel is big, not little; it embraces all of life, not just a little religious corner of it. As he puts it in Ephesians, God’s purpose is to bring all things together in Christ.

But then Paul suddenly veers outside of their religious comfort zone. He's not just sharing nice philosophical thoughts any more; he's calling for a decision of faith.

The vast majority of people more or less agree on the reality of some great but vague deity.

Christianity proclaims that an event has taken place in the middle of human history that brings every person to a critical decision.

“While God has overlooked the times of human ignorance, now he commands all people everywhere to repent, because he has fixed a day on which he will have the world judged in righteousness by a man whom he has appointed, and of this he has given assurance to all by raising him from the dead.” (17:29-31)

…Remember, this whole story began when Paul surveyed all the idol gods of Athens. For him, the God who sent his Son is still the Holy One of Israel, a jealous God who brooks no rivals, an exclusive lover who tolerates no competition.

No other gods, not marble statues of absent gods. Not money, or sex, or institutions, or nationalistic pride, or boasting politicians. This God stands against all interlopers for the minds and hearts of God’s creatures.

After setting the biblical-historical stage (there’s more to the sermon in the extended version), Len pivots to contemporary application.

To understand the full relevance of Paul’s speech for us today, we need to understand something that’s not immediately apparent about the idolatry of the ancient world.

All of those altars to the known gods and goddesses of Athens and Rome. Jupiter, Zeus, Apollo, Mars, and all the rest. They weren’t just expressions of their religious zeal.

The genius of the Roman Empire, and most ancient empires, was the integration of the politics of Empire with the worship of the gods.

Remember when they asked Jesus about paying taxes? He showed them a Roman coin. It likely bore this inscription “Tiberius, son of the divine Augustus.”

In the Roman Empire, religion and politics were inextricably bound together. The whole pantheon was not just some esoteric religion. It grounded the empire in religious devotion.

Those gods and goddesses were the guarantors of the power and success of the empire. And gradually Roman emperors threw off all pretense and took divine status for themselves.

It became one grand religious and political complex to serve the expansion of Imperial power. And to neglect it wasn’t just considered irreligious, but treasonous.

One of the main reasons the early Christians were persecuted was because they were unpatriotic. Because they refused to visit those temples and sacrifice to those deities that propped up the whole imperial religious and political system. Without the imperial cult, the emperor had no clothes.

This tight idolatrous bond of the religious and political was all over the ancient world. And it’s still around today all over the world. From the Hindu nationalists in India, to the Islamic nationalists throughout the Middle East. It’s about the state co-opting religion to prop up its power. That’s how this particular version of idolatry always works.

The church of Jesus Christ has often been tempted to reach for power by cooperating with this idolatry and lending its stamp of approval to the state.

We’ve heard it all before. The divine right of kings. God and country in the Fuhrer’s 1000 year Reich. And today, there’s the message that God is leading America back to its former glory as a “Christian nation.”

That was exactly the idolatry that many early Christians died in resisting.

Ultimately, it’s the old temptation the Devil threw at Jesus. Bow down to me and I will give you the nations of the world. As French theologian Jacques Ellul once said, “When Satan offered to give him all the kingdoms of the earth, Jesus refused, but the church [too often] tends to accept the offer.”

I’m not talking here about whether you’re a Republican or Democrat. I’m not talking about our political differences over economic policy, or international policy, or about who is the best person to lead the nation. That’s all to be expected. And yes, we should certainly love our country and pray for it.

But the one thing the church must never do is to claim God to be on the side of any particular country or any particular political party or any particular individual. That is is the road to idolatry. That is a bargain with the Devil.

There is one Lord who lays claim in love to all people and all nations everywhere. The risen and ascended Lord Jesus Christ.

He, and he alone, is Lord of lords, and King of kings. He alone has the divine right to command the full allegiance of all people everywhere.

Paul felt God’s jealous love for human hearts stirring within him as he surveyed the idolatry of Athens. And be sure about this, the gods of this world are not benign.

They devour individuals and whole societies. They degrade human life. They lure us into insipid pleasures. They set our hearts on things that will not last and will not give true joy and blessing. They herd people into rival tribes rather than bind them together in love and peace. They speak lies and despise the truth.

The church has a gospel to speak to this world filled with idols. It’s the same gospel Paul proclaimed before the Areopagus. Jesus Christ is Lord.

He alone has the right to claim our hearts and lives. He alone is worthy of our heartfelt worship. He alone will lead us to live a truly good human life. He alone will tell us the truth that will set us free. He alone will finally bind all humanity together in mutual love and respect.

That was Paul’s gospel, and that’s our gospel.

For those who want to hear this kind of preaching in the days and months ahead, you can find weekly sermons posted on YouTube or sign up on the church’s website for the mailing list to receive links to the livestream. And please feel free to point us to additional messages and resources in the comments that are helping you navigate this new political and spiritual terrain.

Speaking of which, a reminder for GA friends: I’ll be in Atlanta this Sunday along with several really incredible musicians.

Info and (free) registration here. We would love to see you there.

Since so many are wanting links to access future sermons, I added the info in the text.

This was a very helpful message; thank you. I'm eager to view the whole sermon when I'm home from work.

My wife didn't want to go to church on Sunday, because when she saw that one of the hymns selected was "It Is Well with My Soul" (written in response to the tragic deaths at sea of the author's family), she thought the message would be more in that vein. She wasn't up for it, and neither was I. As it turned out, the sermon touched on Lamentations (in the wake of a national disaster) and was more what this congregation needed to hear. The pastor also found a way to make the lectionary passage from Matthew 20--tying greatness in the kingdom of heaven to servanthood--work in a healing way.

But I knew that the study group I lead after church (African American women are the largest part of the group, which is interesting, considering that I'm an older white male) would want to unburden themselves a lot more about this, so I was trying to find a response that wasn't some "be at peace because God is in charge" pablum but also was more than just venting and spleen.

And I came back to a story I had learned years earlier.

The day after the French government surrendered to the Nazis in May 1940, a Protestant minister in the small town of Chambon-sur-Lignon in southeast France delivered a sermon on how they should respond. He told the congregation that, whenever they encountered orders and authorities that were contrary to the orders of the Gospel, the duty of Christians was to resist, relying on what he called "weapons of the Spirit."

Starting with the congregation, that is what the village did. They began providing shelter to French Jews (as well as Jews from Germany who had fled to France before the outbreak of the war). People took them into their homes and onto their farms and passed them off as relatives who had been displaced from other parts of the country.

As word quietly spread, many more Jews found their way to Chambon-sur-Lignon. The residents began operating an underground railroad to Switzerland. But before long there were several thousand Jews in this area where none had been before--as many Jews, in fact, as Christians. Catholics joined the Protestants in hiding them. People in the surrounding villages also joined what one writer called "a conspiracy of goodness."

Given the sheer numbers, it became nearly impossible to keep the conspiracy a secret. Before long, the local Vichy authorities--whose record in assisting the Nazis round up Jews was notorious--found out what was going on. They chose to look the other way.

Although Chambon-sur-Lignon was far away from fighting, a small contingent of German soldiers was in the area. Inevitably, they discovered the secret. They, too, chose not to report it to their superiors. In this way, the witness and resolve of the local people converted these enemies into co-collaborators for goodness.

Over the course of the 4-year occupation, the operation came close to being exposed several times. A few members of the local resistance were arrested for various reasons, tortured by the Gestapo, and killed. Among them was the Protestant pastor's brother. But not one of the 5,000 Jews who came to the area was betrayed into the hands of the Nazis.

In the 1980s a French filmmaker named Pierre Sauvage came to Chambon-sur-Lignon. He wanted to understand what had happened there and why. He had a personal reason for telling the story. He'd been born there in 1943, while his Jewish parents were under the protection of the locals.

When he began interviewing these simple farm people about why they had risked their own lives and the lives of the whole community (the Nazis practiced collective punishment against entire towns, like Oradour in France or Lidice in Czechoslovakia), he was startled by their answers. "It was the right thing to do," they said. Or: "These were our neighbors, and they needed our help."

You can find Sauvage's film, "Weapons of the Spirit," online. Very few Americans have heard of it. Maybe more will find it now.

That is the story I shared with the Sunday group. Especially now, I want to share it as widely as possible. Innocent people will be rounded up and put in camps for deportation. Families will be split and destroyed. Immigrants will be targeted as "vermin." Black students are already receiving messages that they are now plantation slaves. In my state, simply being pregnant carries a risk of death. We will need an overflow of that rarest of human qualities—moral courage—to resist the darkness.