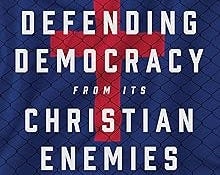

Unflinching in his analysis, David Gushee traces the sobering history of Christianity’s all too frequent complicity in authoritarian rule. Yet Gushee also shows how Christians have within their faith the tools to restore democracy at this critical juncture. Reminding readers that democracy must be fought for, Gushee equips the American church for this b…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Du Mez CONNECTIONS to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.